Running with coronary heart disease: Part One

How running metrics may have helped avoid a bad outcome

A slowdown in my running combined with a fall at home one morning eventually led me to go to the doctor. The result is not what I expected.

The fall in my cardio performance

My running was never better than in parts of 2022-2023 in terms of times, evenness of splits, and how it felt overall. But my performance took a big hit in 2024. My times dropped by at least a minute per mile, sometimes closer to two. For a while, I found it hard to run even a couple of miles without hitting a wall. This after 12 years when I was running at least six half marathons a year.

Initially, I put it down to recovering from a quad or IT band injury that dogged me around the start of 2024. And then to dealing with a third bout of Covid. I wondered whether I had long Covid. But the symptoms were not really typical of post-injury recovery. And, looking back, this all began before I had that further encounter with Covid.

I tried taking iron supplements to see whether that might make a difference. And I also wondered whether — after my 67th birthday in February — the realities of age were simply catching up with me.

So it’s not like I wasn’t thinking about the issue. But somehow it never occurred to me that the dip in my cardio exercise strength could be the result of cardiovascular disease.

Realizing something was up, I scaled back on my running. But as the year progressed, I stubbornly pressed on and I seemed to recover to some extent. I was able to run 10Ks, such as the one in Paris in May, albeit still over a minute per mile slower than before. I did the relay in the Victoria Falls Half Marathon — i.e., half of a Half — with my family in July, again at a slow pace. But all my plans to run an actual half marathon were postponed. The last time I ran 13.1 miles was in Tokyo in October 2023.

Looking back, the slowdown started back in September of 2023. I struggled a bit during the second half of the Copenhagen Half Marathon that month, putting that down at the time to hot temperatures. Tokyo — although better — was still behind my recent average.

A sudden fall

One morning in August 2024, there was a strange incident. Soon after getting out of bed, I sort of passed out and collapsed to my knees. I still can’t quite reconstruct exactly what happened. I was then momentarily aware, vaguely thinking I needed to pick something up, before my face slammed down on the hardwood floor, chipping a tooth and cutting my lip. I felt fine immediately after, other than being shaken.

A preliminary diagnosis

After the fall, I remained in denial. A few Google searches led to reassuring suggestions that this sort of thing can sometimes happen and need not be a cause for concern. As for the ongoing cardio slow-down, I felt I could still barrel through that. Mind over body.

However, about two weeks later, at the urging of my wife and some close friends (one of whom is a physician), I reported the fall as well as the drop in my cardio strength to my primary care doctor. Doing so may have averted something very bad.

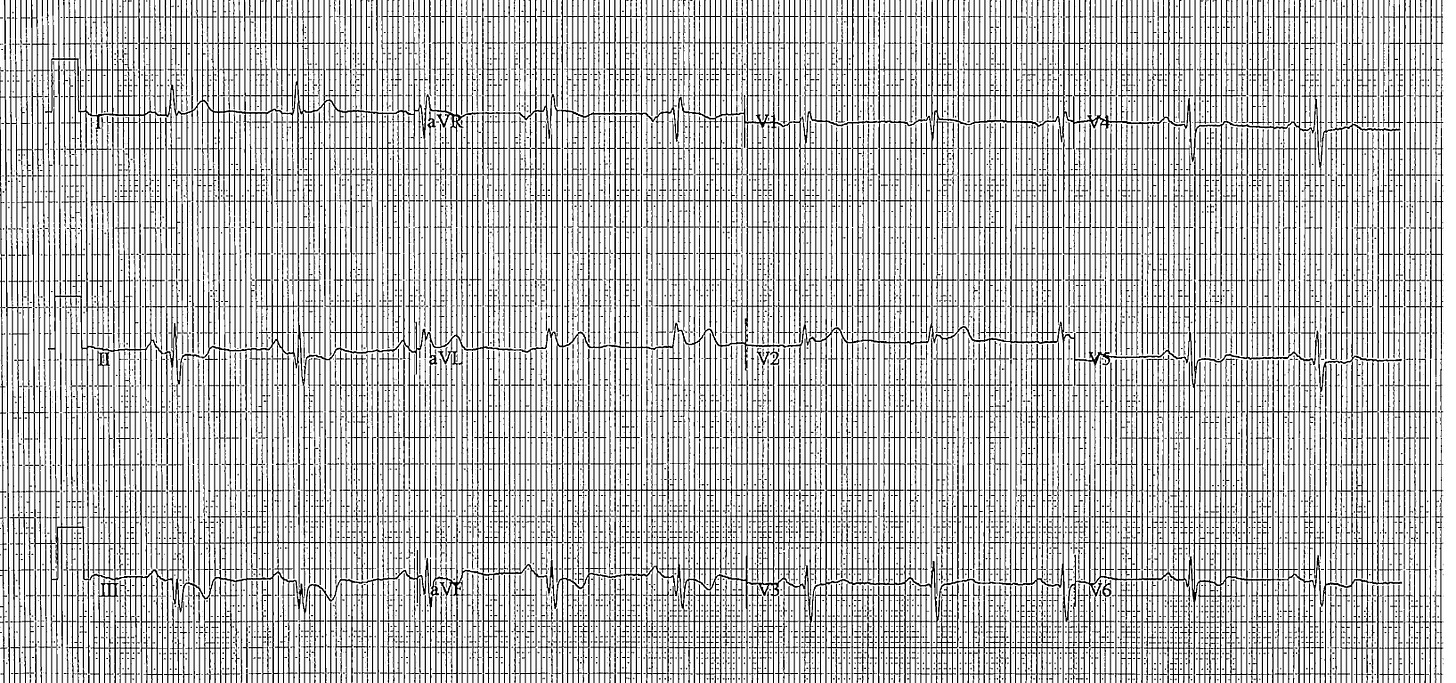

Upon hearing about the symptoms, my doctor immediately ordered an EKG in his office as well as blood work. After looking at the EKG results, he asked his nurse to repeat the test. And then came his assessment: “It looks like you have had a heart attack.” He thought it must have been a silent heart attack, the type you don’t even know is happening. And this likely occurred some months before the fall. The latter could be connected, however.

The news came as something of a shock. When I contacted my doctor, I was expecting he might advise taking some sort of supplement due to a deficiency of some or other mineral. I didn’t consider myself particularly at risk for heart disease.

I follow a reasonably healthy diet. My cholesterol had been pretty good in recent years. I had never needed meds to keep it down. It was a bit elevated during bloodwork at my last annual check-up — which surprised me as I didn’t think my diet had changed — but not by an alarming amount. I hadn’t smoked for well over 40 years (even though I smoked quite heavily for several years during my foolish youth). My weight has been where it should be for over 10 years. And I had also been getting lots of exercise for over a decade. My blood pressure had been under control, albeit with meds. Neither of my parents died from heart issues. My maternal grandfather died of a sudden heart attack, but that was in his eighties. My work can be stressful, but I have lately been changing its focus to make it less so.

So I did not see myself as a likely candidate for heart issues in my sixties. And, on paper, I wasn’t.

The discovery of the culprit

My doctor referred me to a cardiologist. I was instructed to stop running until they figured out what was going on.

A heart echo test — ultrasound — and stress test proved inconclusive. So the cardiologist ordered an angiogram. This is a procedure where they insert a catheter into an artery in your wrist or groin — right wrist in my case — which they then send through your body to check out the arteries leading into the heart. They pump a dye into the arteries and a moving, live X-ray shows where the dye-infused blood is able to flow and where it is partially or fully blocked. It’s an out-patient procedure carried out under sedation and with painkillers (including, at least in my case, Fentanyl, no less).

I had the angiogram exactly two weeks after my primary care doctor first diagnosed a heart issue. Like many, I was a bit nervous going into it, but can report the procedure was not painful or — once it was underway — even stressful or uncomfortable. What it would have felt like without the drugs is another matter.

Despite my sedation, I was aware of what was taking place and after about a half hour, the cardiologist told me she had found the culprit — one of the three main arteries leading into my heart, the one of the right, was 95 percent blocked.

My body was attempting to cope with this by trying to send some blood to the heart using narrow side arteries known as “collaterals.” Apparently, that does not always happen, but the fact I had been running with the blocked artery may have caused my body to try to figure out a way of coping. However — as with traffic leaving a highway to use side streets during slowdowns — this wasn’t helping much.

The fix

When a cardiologist finds a blockage during an angiogram, standard operating procedure is to fix the problem then and there with a related procedure known as angioplasty. This means using a balloon to stretch open the blocked artery and then inserting a short wire mesh tube, called a stent, to keep it open. The stent is left in place permanently to allow blood to flow more freely. So that is what took place. Less than an hour after entering the procedure room, I was wheeled out, the stent — my new life-long companion — embedded in place. The whole angiogram/angioplasty thing is a remarkable high-tech medical procedure.

In the debriefing, the cardiologist advised that this blockage, left untreated, could have resulted in a sudden and potentially catastrophic heart attack. Running with the blockage could have made that all the more likely. She was uncertain whether I had already had a silent heart attack. But the good news is she did not see damage from any that may have occurred. So it seems I dodged a bullet.

The take-aways

My main take-away and advice is that if you experience a sustained, marked decline in your running performance or — if you aren’t a runner — in your ability to do cardio exercise in general, get it checked out. Same goes if you simply find it harder to do what you were able to do previously.

If you leave it too long, you risk life-changing — and potentially life-ending — consequences. Knowing what I know now, I should have gone to a doctor earlier. I was uninformed and, perhaps, in denial.

Another take-away is that my experience vindicates focusing on exercise metrics. Yes, there were times when the issue would have been apparent even without an Apple Watch or similar device recording my running stats. I didn’t need a watch to tell me when I was hitting the wall in under two miles. But the metrics nonetheless provided feedback about the extent of the problem and its sustained, ongoing nature even when I convinced myself I was recovering.

In short, my watch gave me data suggesting something was wrong. The problem is I didn’t properly act on the information.

However, a further take-away is that there’s a limit to how much you can rely on the device you wear on your wrist. Apple itself warns its watch is not able to tell you if you are having a heart attack. And I’m not sure the built-in EKG function would pick up the detail doctors see on professional grade equipment — and, even if it did, a layperson wouldn’t know what to look for. To my untrained eyes, the EKG results on my Apple Watch did not reveal anything untoward when the doctors saw a problem on their equipment.

Someone asked whether I had been “overdoing” the running such that this may have caused my heart issue. Actually, I really don’t run all that much compared with many people. My typical weekly total in normal times is somewhere in the 15-20 miles bracket. That’s obviously a lot more than a couch potato. But I am much more recreational than hard core. A dilettante compared with many.

That aside, the suggestion that running too much damages the heart is misguided (unless, perhaps, you’re talking about extreme amounts). Recreational running is good for the heart. Running does not cause arteries to block. The reason some runners go into cardiac arrest is that they exert the heart when it is already compromised for other reasons, of which they are often unaware.

What now?

I’m writing this less than a week after the procedure. I’m feeling great, but there’s a recovery and rehab program. For now, I generally have to take it easy and not let my heart rate go above 100 beats per minute while the stent settles in and my body adjusts.

However, the good news is that the cardiologist says there is no reason I shouldn’t run half marathons again and be back where I was before all this started. No doubt when I do resume running, I will need to start slowly in terms of distances and pace, just like after any hiatus. That’s not just a heart thing. But, in theory, the renewed full flow of blood to my heart should mean I’ll eventually be back to where I was.

I regard the peak of my recent running to have been in the period between fall 2022 and spring 2023. I did the Munich half marathon in under 2 hours and 1 minute. Not a PR, but close. Berlin was a bit slower at just over 2 hours 4 minutes. But that was in some ways the best race I have ever run, with negative splits on a flat course. (For non-runners, that meant I ran the second half faster than the first.) Istanbul soon after was a bit faster and also well run.

Will I ever get back to that? We’ll see. Part of me wonders whether maybe there was more to my slow-down than the heart. Maybe it was the heart and long Covid or whatever. And maybe age is also a factor. That’s why I titled this post “Part One.”

And although the arteries going into my heart are now all good, there are other important arteries in the body. Not least those connecting the brain. Could it be that one of those has also got blocked? From now on, I’m on statin meds to help prevent blockages in any artery.

Once you are diagnosed with arterial or coronary issues, your statistical life expectancy — as my cardiologist candidly acknowledged — can take a bit of a dip. But there are plenty of success stories where people go on to lead healthy and full lives.

I don’t expect to run a half marathon in the remainder of 2024. But January 2025? Maybe. And in the meantime, there are a bunch of aviation and travel blog posts I have in mind before resuming race reviews. ❤️