Alaska’s inaugural intercontinental flight: Seattle to Tokyo Narita

Understanding the combined Alaska-Hawaiian airline. Plus: A 5K run around Tokyo’s Imperial Palace, and the ins and outs of Japan’s “capsule hotels.”

Inaugural flights — when an airline first operates a flight on a new route — are a bit of a thing, at least in the U.S. There’s usually some sort of event at the gate, sometimes to the bemusement of passengers who didn’t know there was anything special about the seemingly ordinary flight they’d booked.

I’ve been on three inaugural flights, all relatively recently — but only once intentionally. The intentional one, the most recent, was the type that drew a water cannon salute from fire trucks as the aircraft taxied to the runway. More on that shortly.

The first was in 2021, when my son and I were on our way to Anchorage to run the half marathon there. It was my first race after the pandemic shut-down. And my only one in which bears caused an incident on the course, although only runners faster than us were impacted.

We picked a route for that trip that took us from San Francisco to Anchorage on Alaska Airlines. And we had no idea we’d be on an inaugural flight until we got to the gate at SFO. It surprised me that this route didn’t exist already. Alaska has had a significant presence at SFO ever since it acquired Virgin America in 2016. And although Alaska isn’t based in the state after which it is named (it calls Seattle home), it is by far the dominant carrier there with very deep roots.

There was something of a party atmosphere at the SFO-ANC gate, with an energetic master of ceremonies running quizzes and contests yielding decent prizes. My son — still in high school then — won a pair of tickets for a glacier day cruise by having a driver’s license number that included the flight number.

Three years later, I was making my way back from Atlanta to Santa Barbara. Normally, that would be a two-flight trip. But it just so happened that the day on which I wanted to travel was also the first that Delta was to fly that route — which was also the first-ever scheduled nonstop connecting Santa Barbara, my adopted hometown, with a city on East Coast time. An inaugural route like that only gets a fairly low-key gate event. But there were still balloons and cupcakes. The captain gave out Airbus 220 stickers in person.

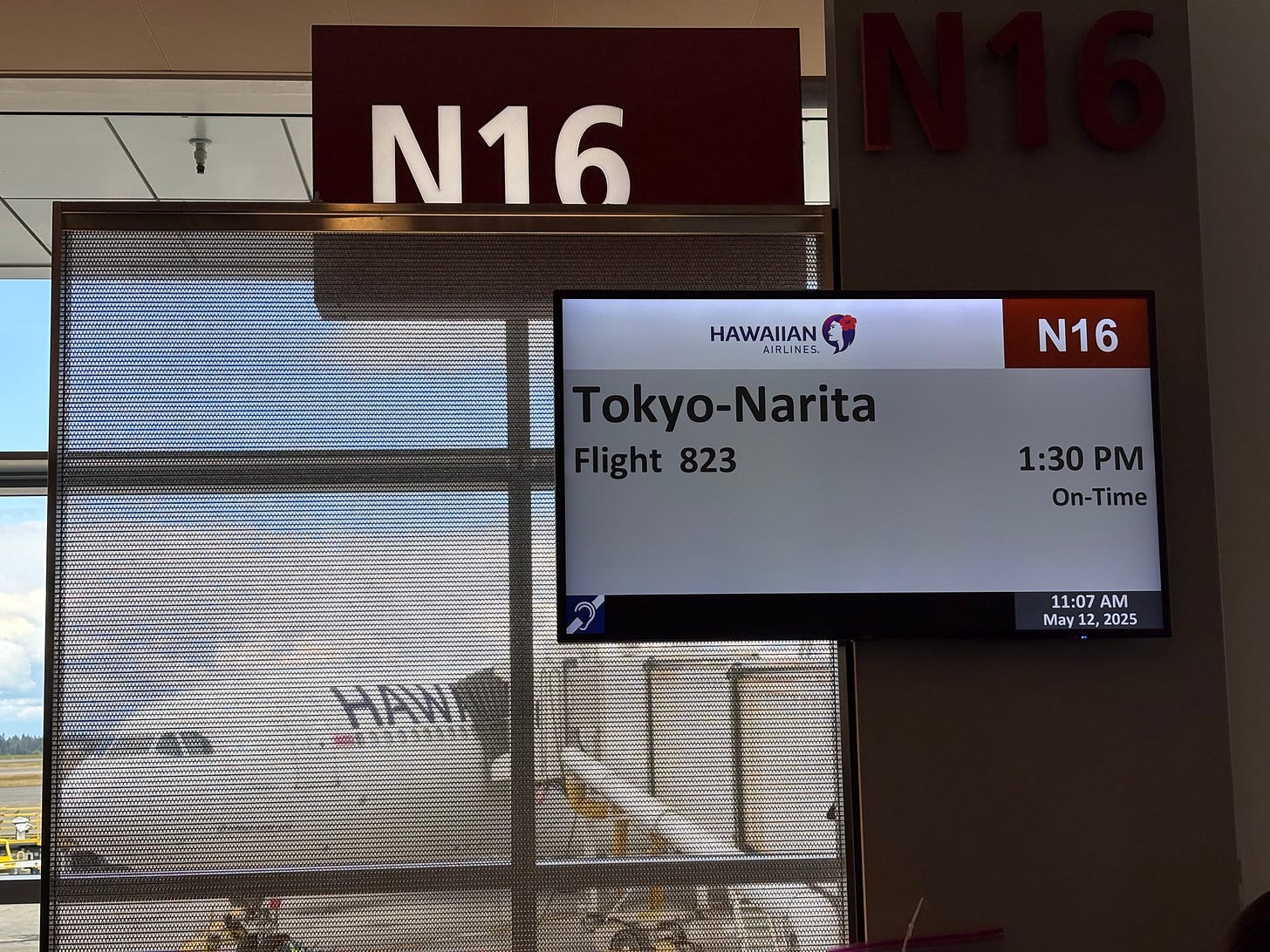

The Alaska-Hawaiian acquisition

My third inaugural flight — in May 2025 — was the intentional one. It brought out the airline top brass to the gate, including the CEO, as well as a live band. I’d planned on taking it for months. But I wasn’t sure about whether I would until the day, as I was standby. This one was a big deal if you’re an inaugural flight aficionado: Seattle to Tokyo, Narita. Other airlines have flown that route before. But it was Alaska Airlines’ first-ever intercontinental flight from its Seattle hub. At least, sort of — as I will explain.

Alaska recently acquired Hawaiian Airlines. The acquisition is complete, but the process of merging the two operations is still a work in progress. At the time of writing, Alaska Airlines and Hawaiian were still two separate airlines with the same parent company — Alaska Air Group (which also owns Horizon Air, Alaska’s regional carrier, and McGee Air Services, a ground operations company).

Soon, however, Hawaiian will be merged into Alaska Airlines, with a single FAA operating certificate, but with both the Alaska and Hawaiian names and liveries continuing to co-exist. The merged corporate entity will be Alaska Airlines. And the corporate family tree will look no different from before the acquisition, with the enlarged Alaska Airlines remaining a subsidiary of Alaska Air Group. But Alaska will keep the Hawaiian name alongside its own.

Airline takeovers and mergers are nothing new. But usually, names go away. When United acquired Continental, the latter’s name was relegated to the museums of aviation history. Same when Delta acquired Northwest. And when United and Delta parsed out the various bits of Pan Am. Or when American acquired what remained of TWA. And so forth. But this one is conceptually different. Both airline names will survive.

Under the merger, flights to and from — and between — the islands will continue to be Hawaiian-branded, at least for the most part. Other routes will be flown under Alaska livery. But it will nonetheless be one airline. Not two affiliated airlines with common ownership and some shared resources, but a single, fully integrated operational entity. There isn’t a precedent for that elsewhere in the industry.

Some pundits have mistakenly analogized this to sibling airlines such as British Airways and Iberia, or Air France and KLM, or Lufthansa and Swiss. But those analogies miss the mark because they are examples of affiliated but operationally separate airlines under common ownership. Here, at the risk of laboring the point, there will be one operation, albeit with two customer-facing brands.

Some think the “one airline, two brands” approach risks confusing customers. But making “Alaska” the face of Hawaii wouldn’t have made sense. Adopting “Hawaiian” as the name of the combined airline would have made even less sense. And inventing a completely new name — Pacific Airlines was among the more obvious suggestions — would have meant shutting down two iconic airline brands with deep roots and loyal followings.

There were times when the rumor mill surmised a tripartite merger involving Alaska, Hawaiian, and JetBlue. That might, perhaps, have resulted in a combined airline with a name like — my guess — “Pacific Blue.” But that never happened and doesn’t seem likely at this point with JetBlue pursuing a loose alliance with United after its dalliances with American and Spirit fell apart for one reason or another.

Might some new name for the combined Alaska-Hawaiian operation eventually come about? Maybe if one speculates about possibilities 10 or more years out. But Alaska is investing much in the dual-brand strategy. So I wouldn’t expect it to change in the foreseeable future.

What’s happening now with Alaska and Hawaiian?

Before the acquisition, Alaska had always been an all-narrow-body airline. Its international operations were limited to Canada, Mexico, Central America, and, briefly, the Bahamas. But Hawaiian, although the smaller of the two, flew some longer distances and had a mixed narrow- and wide-body fleet. Its wide-bodies plied some of its more heavily traveled routes between the islands and the U.S. mainland. And it also had — and continues to have — a route network connecting Honolulu with destinations in Asia and Australasia.

Hawaiian’s wide-body fleet long consisted of Airbus 330s. But the airline has taken delivery of the first three of an order of around a dozen Boeing 787 Dreamliners, which Alaska has since extended with options that would bring the total to 17 in the coming years.

Not long after the acquisition, Alaska announced that it would redeploy some of the wide-bodies that came with Hawaiian for long-haul intercontinental operations out of Seattle under Alaska livery. And that is how I came to take this inaugural flight — the route to Tokyo is the first of these.

Earlier, I qualified my reference to this being Alaska’s first intercontinental flight by saying “sort of.” The flight was widely referred to as its first intercontinental one, including on the inaugural swag. But, at this stage of the merger, the flight was actually operated on Hawaiian Airlines metal — and with Hawaiian Airlines crew. Once the merger is complete, and the two hitherto separate airlines are on one FAA operating certificate, the intercontinental flights out of Seattle will be Alaska-branded.

But this inaugural flight was nonetheless a big deal. Even if you do view this route as, for now, more “Hawaiian” than “Alaska,” it still marked the entry of a new airline to the transpacific market out of the mainland U.S.A. And it has been a long time since that has happened.

Where next for Alaska?

Even before the Hawaiian merger, Alaska was already the world’s 13th largest airline if you measure by the number of flights operated every day (as opposed to, for example, passengers carried, miles flown, or revenues earned). On that measure, indeed, Alaska comes out significantly ahead of global carriers like British Airways and Lufthansa. And it will rise to around number 10 after the Hawaiian merger is complete.

But the airline will become larger still. Alaska has stated that it intends to serve a dozen intercontinental destinations out of Seattle by the end of the decade. Seattle is well placed geographically. Flight times from Seattle to Europe and parts of Asia are shorter than from San Francisco and Los Angeles. So the city is well positioned in the top-left corner of the U.S.A. to pick up connecting traffic.

Alaska’s next destination after Tokyo will be Seoul. That route will start in September 2025 (and is already served by Hawaiian out of Honolulu). And then starting in May 2026, Alaska will launch service to Europe. Its first European destination will be Rome.

Rome was an interesting choice. It has long been an under-served market from the U.S. West Coast. But it is also not a destination where Alaska — part of the One World Alliance — will have an existing partner for connecting traffic.

Before Alaska spread its intercontinental wings, Delta was the only U.S. airline operating long-haul international flights out of Seattle. American had planned to move into the market a few years ago in an alliance with Alaska, but most of the planned destinations — including Bangalore, India — never materialized, and the London route that did take off proved short-lived. Delta responded to Alaska’s Rome move by announcing its own Seattle-Rome service, which will launch a few days before Alaska’s. Furthermore, Delta announced a new Seattle-Barcelona service starting around the same time, the first to that city by any U.S. airline out of the West Coast. So Delta is clearly signaling that it doesn’t intend to make intercontinental life easy for Alaska.

It’s anyone’s guess as to what other intercontinental destinations Alaska has planned. The destinations already served by Hawaiian out of Honolulu could be obvious choices. Those include Tokyo Haneda, Osaka, Sydney, and Auckland. London is already served out of Seattle by Delta, British Airways, and Virgin Atlantic, but it’s hard not to imagine it is high on Alaska’s list — especially as British Airways, also a One World carrier, could be a partner. But slots at London Heathrow can be hard to come by. London Gatwick could be a dark-horse contender, notwithstanding its reputation as the city’s B-list airport. I don’t believe any major U.S. airline has ever served Gatwick out of the West Coast.

Madrid could be a contender if Alaska wants to leverage One World synergy with Iberia, BA’s sibling airline. No U.S. airline currently flies to the Spanish capital from the West Coast. Hong Kong is another possibility, again because Alaska would have a One World ally, Cathay Pacific. Taipei is a heavily travelled route from the West Coast, and so that, too, is a possibility.

And maybe there could be some dark horse surprises. Lisbon, anyone? Or, indeed, Barcelona, if Alaska wants to show Delta that it can give as much as it gets. Vietnam? No U.S. airline yet flies there nonstop, but there is a strong Vietnamese diaspora on the West Coast. That’s a long shot, even though I think it would just about be within the range of the 787.

The inaugural flight experience

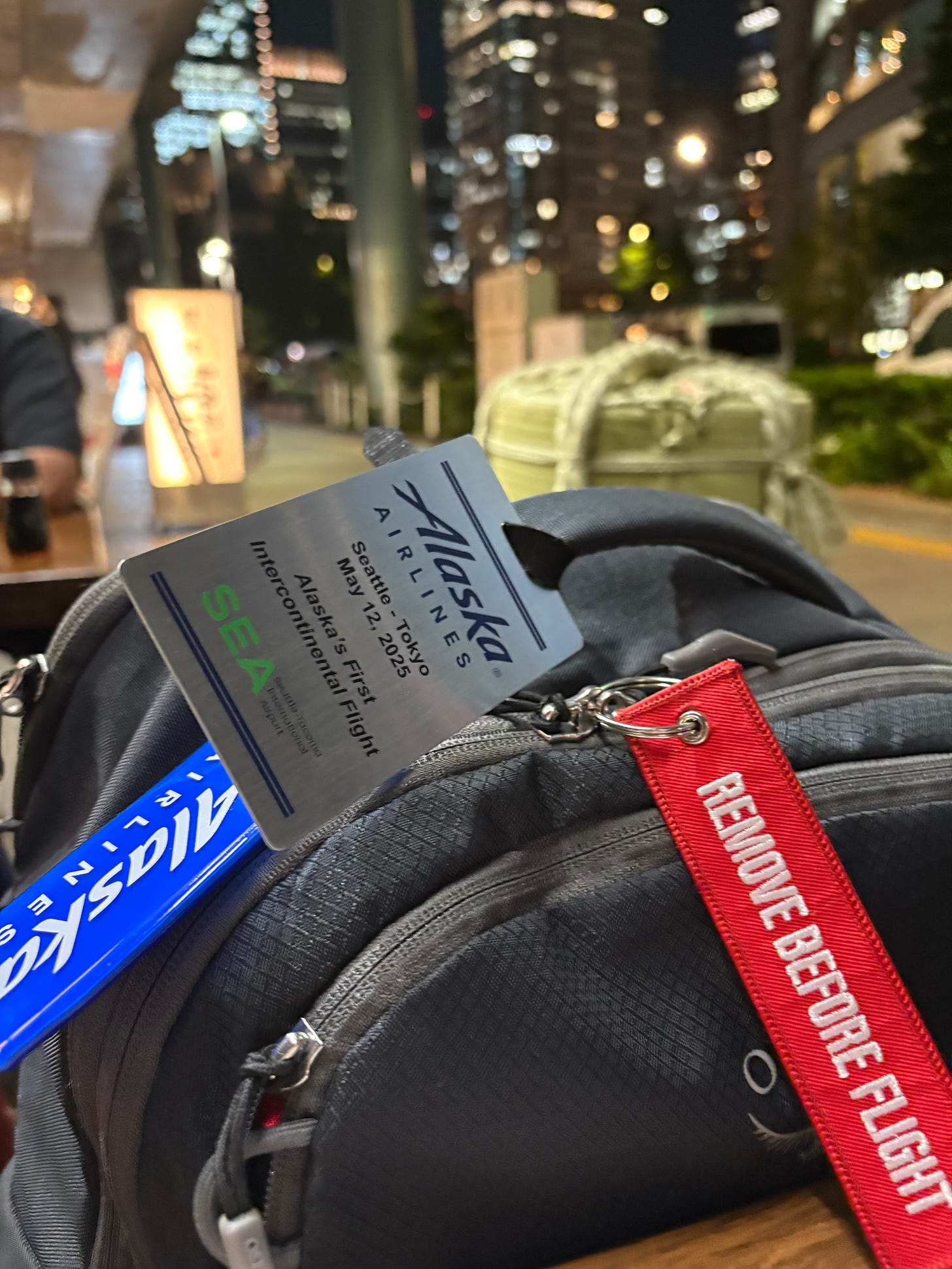

As a nod to the fact that the Seattle-Tokyo flight was still being operated under Hawaiian livery, the gate festivities started with a Hawaiian music performance. That was followed by speeches from Alaska’s CEO and others and a ribbon cutting. There were also Japanese mochi treats. Onboard, there was some swag awaiting passengers on their seats, including a luggage tag memorializing the flight (pictured at the start of this post).

The Seattle-Tokyo flight is initially being run on an Airbus 330. In a way, it was surprising that Alaska did not deploy one of the newer Hawaiian 787s for this landmark route. The latter are equipped with a more up-to-date Business Class with a 1-2-1 seating configuration, as opposed to 2-2-2 on the A330. I imagine there were operational and/or regulatory reasons why the 787 was not ready for the route.

Personally, I like the A330, because of its 2-4-2 configuration at the back of the plane — those rows of two are great if you are traveling with a friend or loved one (not that I was on this occasion). Business Class on the inaugural flight had been booked out months in advance, largely blocked for press, I believe. So I was happy to get an aisle in the center row in Economy on what was a pretty full flight (I was far from the only non-rev traveler wanting to experience the inaugural flight). The couple next to me hadn’t realized they were boarding a “special” flight. They had just picked it on Kayak.

As the plane taxied from the gate area, there was the water cannon salute from fire trucks that I mentioned earlier — a tradition reserved for landmark flights, but not routinely given out to garden-variety inaugurals. Once airborne, however, it became a regular sort of Hawaiian flight, except for a roaming camera crew that occasionally appeared.

I’d already flown transpacific on Hawaiian to Japan earlier in the year, when I went to Osaka via Honolulu. And I really like the airline. The service I experienced on all the Hawaiian flights I’ve taken this year has been great. I’ve found the food on the international flights to be above average for Economy, both in terms of quality and quantity. It has an Asian emphasis. Wine and beer are free on those flights (as are spirits, at least on the initial drinks service). And not only is the WiFi also free, but it is super-fast Starlink WiFi, which works on the ground as well as in the air. (Starlink isn’t yet available on the 787s, but is coming.)

Up front for the return

I was only in Tokyo for 24 hours. Enough time for a run around the Imperial Palace, of which more shortly. Coming back, on what was then the second Narita-to-Seattle eastbound flight, I was seated in 2D. As noted above, the Hawaiian lie-flat Business Class on the A330 is not the most up-to-date with its 2-2-2 configuration, but I thought it was an excellent flight nonetheless. Very comfortable. Really good food. Lanson champagne — always one of my favorites (reminding me of British Airways in the eighties and nineties, when it was a staple). Highly professional service.

If you are in the center aisle, you don’t experience the drawback of the 2-2-2 layout in terms of aisle access for everyone. And I found it was private enough. Indeed, on the leisure-focused routes Hawaiian flies, many passengers might actually prefer two-abreast seating on the window.

The Honolulu option remains

Notwithstanding the focus now on Alaska’s new long-haul operations out of Seattle, one shouldn’t forget the option of flying between the U.S. and Asia or Australasia on Hawaiian via Honolulu. It’s obviously not the fastest way. And going to, say, Tokyo via Honolulu means taking a bit of a dip to the south. But it can be an agreeable routing if you have some extra time. You split up the flying. You could enjoy a break on the islands. And I like the Honolulu airport, with its breezy walkways and open-air, airside Japanese garden. As I noted in my recent Osaka post, Honolulu — with the blend of its own unique culture and distinct Japanese influence — makes for a good segue from the U.S. mainland to Japan.

What else might be coming?

The existing Hawaiian long-haul product that Alaska is taking over does not include a Premium Economy class in the sense that most major airlines have one these days on wide-bodies — i.e., with seats that are more like domestic First Class as well as upgraded catering. Instead, it has an “Extra Comfort” section, where the seats have more legroom and power outlets (in addition to USB), but are otherwise the same as in regular Economy.

Alaska has indicated plans to introduce a “proper” long-haul Premium Economy cabin. This will debut on the 787, but it might also come later to the A330. Details will follow in the months ahead — probably in 2026 — along with an announcement of other enhancements to the new long-haul product.

No doubt, Alaska will also harmonize the customer experience on the two brands on both domestic and international operations, while still retaining the distinct nature of each. For example, Alaska currently gives free alcohol on domestic flights to passengers seated in the domestic Premium Economy section of its narrow-bodies, while Hawaiian does not distinguish between “Extra Comfort” and regular Economy passengers when it comes to alcohol on any of its flights. Likewise, Hawaiian, as noted, offers free WiFi, while Alaska charges. Things like that will, I suspect, become standardized.

What about the call sign?

One interesting detail for aviation geeks to watch is what call sign pilots will use when communicating with air traffic control once there is just one airline on a single operating certificate. Currently, Alaska uses “Alaska” followed by the flight number, while Hawaiian uses “Hawaiian.” Generally, the call sign reflects the operating certificate on which a flight operates, not the livery on the outside of the aircraft. For example, Horizon regional jets flying under Alaska paint have a “Horizon Air” call sign, as the airline — although wholly owned by Alaska Air Group — flies under a separate operating certificate from Alaska Airlines itself.

So it is not clear that the Hawaiian call sign will continue to exist. But whether pilots flying Hawaiian-branded metal will simply use the “Alaska” call sign or whether the combined airline will come up with something else remains to be seen. Call signs do not have to match the name of an airline — as, for example, with British Airways, whose call sign is “Speedbird.”

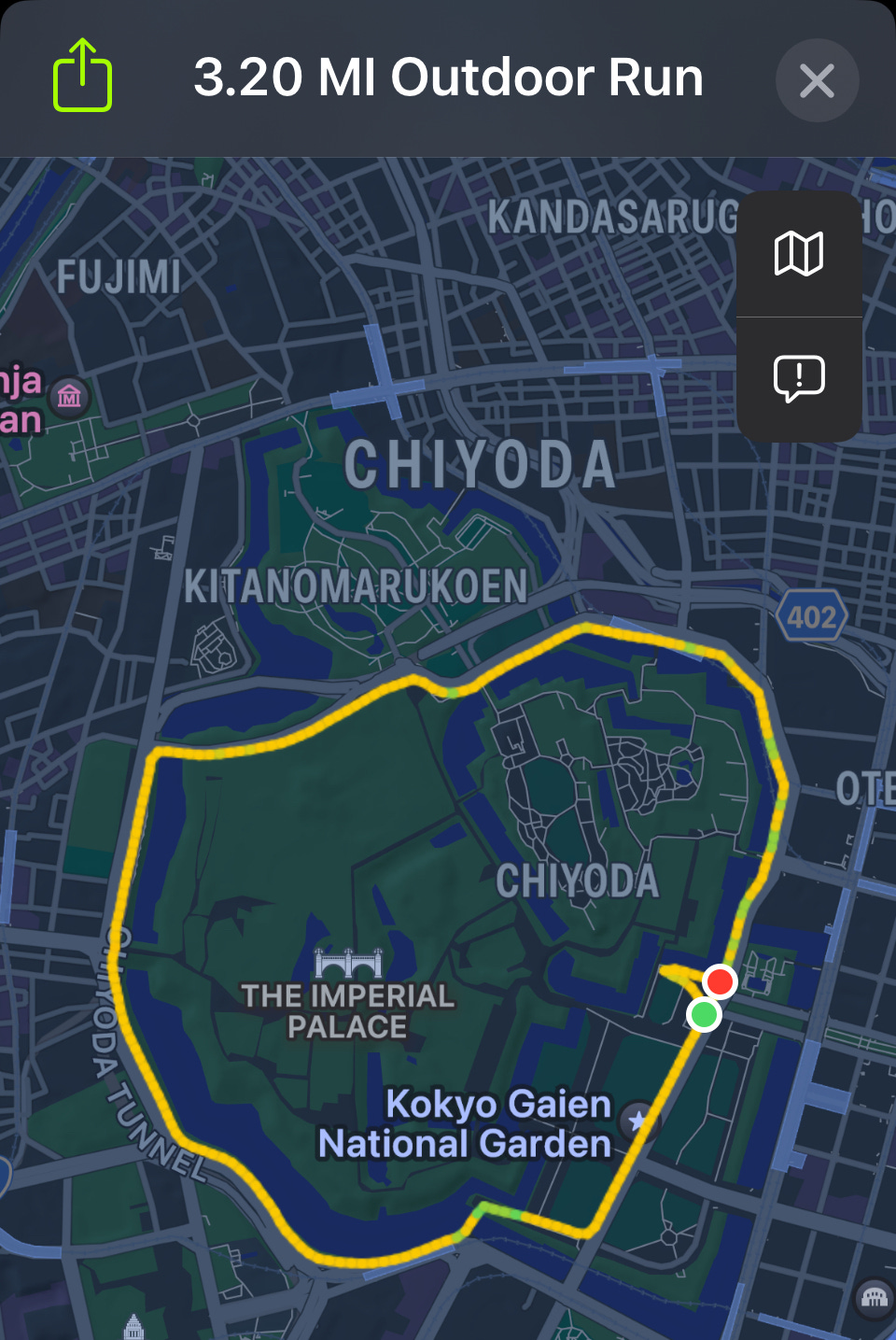

A run around the Imperial Palace

I was only on the ground in Tokyo for 24 hours. My running mission was to do a loop around the Imperial Palace. I doubt that the Shoguns or Emperors designed the contours of their palace with runners in mind, but it just so happens that a full circumference on the multipurpose path around it amounts to almost exactly a 5K distance. Perhaps for that reason, the Imperial Palace loop is the most popular running route in central Tokyo.

Not long earlier, I’d done a run around Osaka Castle, which is a somewhat similar experience. I realize that not many people other than me would fly across an ocean to Japan principally in order to do a 5K or 10K run around a palace or castle — especially when it isn’t even part of a recognized running event. But if you are such a kindred soul — or happen to be looking for running opportunities while in Japan for other purposes — I’d say Osaka Castle is actually the better pick than Tokyo’s Imperial Palace. Although I wholeheartedly recommend either, a run around Osaka Castle gives better views of the destination landmark than one around Tokyo’s Imperial Palace. And Osaka Castle also provides more options in terms of paths so as to vary your distance without simply doing multiple loops.

In my write-up about the Osaka run, I described a nearby facility — a sort of running base — where runners can change and use lockers and take showers. There’s a similar place in Tokyo close to the Imperial Palace, which is run by ASICS, the Japanese sportswear company. I used it and would definitely recommend it, although it didn’t have quite the charm of the Osaka equivalent with its own café.

The Imperial Palace loop is not entirely flat, but that adds to its variety. The etiquette is to go anti-clockwise. You can obviously join the path at any point, but there are some ancillary parts to the whole palace area, so it wasn’t initially obvious whether I was on the 5K perimeter path or some other path. But if you look for other runners, you should be able to figure it out. The photograph below shows the vista where I joined the path at a point close to the ASICS facility, and that might help you to assess whether you’re in the right place. This part was a regular sidewalk, but most of it is its own track.

Capsule hotels

On this short trip, I thought I’d try out something I’d been planning on experiencing for a while — one of Tokyo’s “capsule hotels.” These provide sleeping pods that are somewhat capsule-shaped, often stacked on top of one another on two levels.

In the purest form, there is no furniture. You just climb into your pod, which has a mattress, pillow, sheets, etc. The pod does not have a lockable door, but it does have some sort of a shutter or curtain. You definitely can’t stand up. Capsule pods are purely for lying down and, maybe, sitting up. They typically offer electrical and often USB outlets in each capsule as well as a reading light and there’s WiFi. There are also lockers in a common area where you can put stuff you don’t want to take into the pod.

Capsules are for one person only. You could theoretically squeeze in an intimate partner, but that is not how they are sold and the rules don’t allow for that. In most facilities, there are separate pod areas for males and females. In the nature of the capsule experience, you don’t have your own bathroom, but there are shared ones.

Capsule hotels suffer from a reputation as the refuge of drunken office workers who have missed the last train home. And there may be a bit of that, especially with the cheapest ones in the vicinity of railway stations. But there are also others that try to create a more cool environment, even to the point of leveraging the similarities between capsule sleeping in a city and Business Class sleeping on a plane. In fact, I would say — and I happen to be writing this in the luxury of United Polaris on a flight to Australia — that a good capsule hotel is probably a bit more physically comfortable and private than long-haul Business Class. But, of course, it lacks the same exclusivity and you don’t have someone bringing you roasted sea bass and champagne, etc.

I narrowed my selection of capsule hotels to two chains, which present themselves as among the most “upscale” in the realm of such places — Nine Hours and First Cabin. I went with the Nine Hours location in the Akasaka district. It was a surprisingly nice-looking building on a quiet street. First Cabin — the one that leverages airline imagery most expressly — offers a choice of “cabins,” as they call them, and some of the better ones sort of become more like mini rooms rather than actual capsules. But I wanted to experience the purer form of capsule establishment on this occasion.

Overall, I found it a satisfactory experience. Narita airport is quite a way to the center of Tokyo, and by the time I got there — by regular train — it was early evening. I was traveling very light, so I spent several hours exploring, checking out the lay of the land for my run the next morning, and getting dinner.

There’s an area around Tokyo’s rather grand, Victorian railway station — which is itself near to the Imperial Palace — with countless small restaurants and bars, many under elevated railway tracks or arches or in small alleys. They are popular with office workers — suited “salarymen” as people used to refer to them, although the term has become dated. I hung out in a couple, one specializing in yakitori and the other emphasizing sushi.

From there, I went to the capsule hotel to check in. Once installed, I went to sleep. I got up pretty early and took a shower — even though I knew I’d be taking another at the ASICS place after my run — and then left. That is the best approach to capsule hotels — use them as a place to sleep and not much more (although some do offer lounges and even cafeterias).

I paid just $38 for my sleeping quarters, booking through Expedia. The place was clean. And adequately comfortable. I wasn’t bothered by noise from other guests. Hopefully I didn’t snore so that others were bothered by me — the capsules are not fully soundproofed. I’m not sure I’d routinely stay in a capsule hotel for two nights in a row — and there is generally no access between around 10 a.m. and mid-afternoon — but there’s a lot to be said for them when you just need a place for a night and plan to arrive late and leave early.

Capsule hotels are rare in other parts of the world. I’m not aware of any in the U.S.A. But I did spend a night in one close to the Vancouver airport recently when I landed around midnight on my trip to run the half marathon there (although that one cost more than double what I paid in Tokyo).

Coming next: Australia, and the Run Melbourne Half Marathon. ✈️ 🏃

If you’ve stumbled across this post, please consider subscribing to this blog using the button below. It covers the intersection of running, travel, and aviation, and includes race reviews from around the world. Subscribing costs nothing — and never will — but supports the site. You’ll get an email every month or two with new posts.

For a list of other recent posts, click here.

And please share this post with others who may be interested, using this button: