A ZED fare primer

The ins and outs of “non-rev” staff travel on other airlines. Plus: Why do airlines extend flight benefits to people from other carriers?

A major perk of working in the airline industry are the travel benefits. Many airlines — including all in the U.S. — offer unlimited standby travel on their own flights to employees and partners/close family. But one of the unique aspects of this industry is that most airlines offer great deals to people who work for other carriers.

About this blog post

This post is about the ins and outs of staff travel on airlines other than the one for which you or your loved one works. A significant number of subscribers to my blog do work for airlines. But if you aren’t eligible for airline staff travel, you might still find this post interesting — especially if you or someone you know has ever thought of working for an airline.

And if you already qualify for staff travel, this post might help refine your standby skills, as it includes some pointers about navigating the system around the world. Even though I’m an experienced user of staff travel benefits, I find there’s always more to learn. For example, a chance conversation with someone at Newark airport earlier this year led me to discover how to ride on repositioning private jets in Europe using staff travel benefits. More on that later.

This is a long post. I thought of breaking it up into more than one, but decided to put it all together so as to create a one-stop guide. The post is written from the perspective of U.S.-based travelers, but much of the content will be relevant wherever you are.

One quick disclaimer: Pilots and flight attendants working for U.S. airlines have an option not covered by this post. That is to “jump seat.” Jump seating does not necessarily involve literally sitting in a crew jump seat. If there’s room in the cabin, jump seaters are offered a regular seat. Jump seaters don’t pay any fare at all when traveling on other airlines (although they do pay taxes for international flights). But this is generally only available to U.S. crew members who are traveling off-duty on U.S. carriers (and even then it is more restricted on international flights). As far as I’m aware, no overseas airlines accept other-airline flight-deck jump seaters. So this post is about the options other than jump seating.

Why do airlines offer standby seats to people from other carriers?

I’m not aware of any other industry where companies offer benefits to employees of competitors in the way airlines do. Employees of Netflix don’t get discounted subscriptions to Hulu. People who work for Trader Joe’s don’t get special deals at Whole Foods. Tesla employees don’t get staff discounts on Fords.

But, yes, those who work for an airline generally get very inexpensive standby travel on other airlines — including, fairly often, in premium cabins. And this doesn’t just apply to airlines that are part of the same alliance. The reciprocity also exists between airlines that are outright competitors — American and United, for example, or Lufthansa and British Airways.

The reasons for this unusual arrangement run deep in the fabric of the industry. It’s partly to do with the fact that crew members often commute to work. Your Los Angeles-based flight crew, for example, might consist of people who actually live far afield. Airlines depend on commuters for staffing. So access to other airlines helps get people to work. And that benefits everyone — including, indeed, revenue passengers who depend on airline crews to operate their flights.

But that doesn’t explain why airlines offer flight benefits to employees of other carriers who generally don’t commute by air, such as ground and office staff. Nor does it explain why they offer them to family members and loved ones.

So perhaps the wider explanation is that this is a relatively inexpensive way for airlines to give valuable benefits to their own employees in an industry where — historically — salaries have often been low. Sometimes, indeed, shockingly low (though less so than in the past, at least in some segments). An empty seat on an airplane is a wasted asset. But it is also worth a lot. And it costs little to offer it to someone from another airline moments before it will expire — just a tiny amount of added fuel and, perhaps, some catering. By offering empty seats to people from other carriers for a nominal fare, the airline can gain valuable reciprocal benefits for its own employees for little actual cost. That helps with hiring and retention.

Then there is the fact that the bean counters in the airline industry benefit personally as well. In the U.S. and many other countries, flight benefits go to everyone working for an airline, not just the employees who crew the aircraft. If you work for an airline for long enough, the benefits can accrue for life extending into retirement. So who would want to rock the boat?

Airlines could, in theory, offer standby fares to everyone, not just airline employees, in order to try to fill empty seats. Indeed, there was a time in the 1980s when they used to do just that on transatlantic routes to and from the U.K. (although not for fares as low as staff ones). But opening up standby travel to the masses would mess with market prices by discouraging price-sensitive travelers from booking ahead. In addition, standby travel can pose logistical issues when it comes to processing passengers at airports. So it makes sense for airlines to restrict the standby field to staff.

Why would airline employees want to fly on other airlines?

A surprisingly large number of eligible people rarely take advantage of standby staff travel on other airlines. This is especially if they work for an airline with a very extensive route network on “own-metal” (the term that refers to one’s own airline). If your own airline will take you somewhere for free, why pay anything — even a nominal amount — to go on another?

There’s something to be said for that approach, especially if you work for a big airline with a global route network like United, British Airways, or Lufthansa. That said, restricting your travel to own-metal can mean missing out on interesting experiences.

Flying on different airlines is part of the overall travel experience. Taking almost all your flights on the same airline can become dull, no matter how good it is. In addition, sticking to own-metal can limit your range of options even on airlines with extensive international routes. I’ve flown to many places in recent years to which no U.S. airline currently flies — Turkey, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Indonesia, Surinam, Ethiopia, Lebanon, Iraq, Egypt, Saudi Arabia. And if your airline is one whose routes are focused mainly on short-haul, narrow-body travel, then sticking to own-metal really limits your horizons.

Not everyone’s idea of fun?

Still, not everyone wants to travel standby at all, let alone on another airline where you have lower priority. Many airlines give employees a limited number of confirmed travel, own-metal passes each year and some people choose to stick with only those. That is a legitimate choice. Standby travel can open up wide horizons, literally, but it can also be stressful.

At its best, you can end up swilling champagne in a lie-flat pod on a plane headed to your intended destination. But you can also end up with a middle seat in coach — perhaps not even headed to quite where you actually wanted to go. Or, indeed, left behind at the gate as the last flight of the day pushes back without you. And traveling standby on other airlines can be especially stressful because of lack of familiarity and lower priority.

I personally relish the adventure of standby travel, and the opportunities it provides for spontaneous and flexible travel all over the world. And I enjoy honing my skills at the game that’s involved. But I get it that it’s not everyone’s idea of fun. And not everyone has the flexibility and other wherewithal to deal with the risks inherent in long-haul standby travel.

Nonetheless, although much has been written about how flights are generally fuller now than in the past, there are still times of the year when you can travel on flights that are very empty in the back — even if they are full at the front. And by “very empty,” I mean 100+ seats open at the back. I had that very recently flying from Los Angeles to London and last year going from LA to Sydney. Look for low-season opportunities on routes that maintain year-round high capacity. This post will talk about checking loads in a bit.

Introducing ZED fares

Jump seating aside, in order to travel standby on another airline using staff benefits you almost always have to buy something called a “ZED fare.” ZED stands for “Zonal Employee Discount.”

ZED fares came about as a result of a multilateral agreement for airline staff travel entered into in 1994 by Aer Lingus, Air Canada, Austrian Airlines, British Airways, Lufthansa, Malév Hungarian Airlines and SAS that replaced an earlier staff travel system. Today, over 170 airlines participate, including most major long-haul carriers. Employees of participating airlines — as well as certain family members — can fly standby on other participating airlines for very low fares.

All U.S. airlines participate in the ZED system. But in some parts of the world, not all airlines do so. For example, in Europe, ultra-low-cost carriers generally do not. In Asia, Singapore Airlines is a notable holdout.

ZED — not literally “non-rev,” but almost

ZED fares are part of the “non-rev” system. “Non-rev” is short for “non-revenue” and is an umbrella term covering airline staff travel in general. However, unlike travel on one’s own airline, which is often — and, in the U.S., always — free (other than international taxes), ZED travelers do contribute a little bit of revenue.

ZED fares can be used for both domestic and international travel. The fares are flat rate based on distance. There are nine different distance bands. So the amount you pay depends on the distance you fly. But that is with two important qualifications.

The first is that there are actually three ZED prices for each mileage band — ZED Low, Medium, and High. There is also something called “ZED Zero,” where the fares are, indeed, zero dollars, but this is quite rare and it usually exists only between airlines that, while separate, are very closely wedded. The other qualification is that taxes and fees are added on top of ZED fares.

All ZED fares are standby. There is no such thing as a “positive space” — i.e., confirmed seat — ZED fare. (In other words, there’s no ZED equivalent of the deep-discount confirmed travel that some airlines offer to their own employees.) However, as discussed later, what “standing by” actually entails — and how far ahead of departure you are confirmed if you get on — can vary from airline to airline and, indeed, flight to flight.

Most often, ZED fares are only good for Economy/Coach Class travel. But there are also ZED Business fares — again with Low, Medium, and High bands — that get you into U.S. domestic First Class or long-haul Business Class (or, failing that, Premium Economy). However, as discussed later, you can’t count on qualifying for Business on a given airline just because you do for Economy.

What do ZED fares cost?

Unlike regular air fares, ZED fares are not seasonal or load-related. You pay the same regardless of the time of year or how full the flights are. And they are not set by individual airlines, except to the extent that each carrier can choose whether to charge in the Low, Medium or High bands. So, for example, a ZED Low between, say, Los Angeles and London will be the same whichever airline offering that fare on that route you choose.

ZED Low Economy fares range from $15 for flights of up to 450 miles to $99 for ones between 7,101 and 9,999 miles. This information was current as of fall 2024. ZED fares tend not to increase very often.

However, those are the fares excluding taxes and fees. The fees charged by the booking platforms are modest (a few dollars), but the taxes can add up. For example, the $15 ZED fare for a short flight will likely be around $26 in terms of the bottom line for flights within the U.S.

What you pay for tax depends mainly on the origin, not the destination. As an example, a San Francisco to London flight in ZED Low Economy, which falls in the 5,000-6,100-mileage band, prices out at $69 for the fare itself, but the total you pay is about $97 — so almost $30 more with tax. Still a fantastic deal, nonetheless. Business on that route is $214 without taxes and $244 with.

But taxes for international flights into the U.S. are generally a fair bit more than for those outbound. The highest taxes are those for flights out of London Heathrow. That $97 fare, including taxes, for San Francisco-London becomes $299 when the route is flown in the other direction — three times as much. And London to San Francisco in Business is $444, more than twice as much.

However, Frankfurt to San Francisco (a route in the same mileage band) is $222 in Economy, and $367 in Business — still more than the eastbound flights out of the U.S., but not by as much. So the bottom-line cost for a flight segment can vary quite lot by point of origin. The least expensive gateway city in terms of taxes when flying to the U.S. from Europe that I have found is Copenhagen. Flying from Copenhagen to San Francisco is $142 including taxes, which is less than half the cost from London.

I mentioned the point of departure generally determines the taxes. However, there are exceptions. ZED fares from the U.S. to Mexico are higher than those to Europe, even though the distance is much less. For example, San Francisco to Mexico City with Economy ZED Low is $104 including fees, more than the fare to London. In that example, the ZED fare itself is just $39 and the taxes and fees make up the rest.

Non-revs who travel internationally on own-metal for “free” still have to pay the taxes, incidentally. So on those transatlantic Economy examples, own-metal travelers are only $69 better off than ZED fare riders — although the own-metal travelers have other important benefits, such as priority on the standby list and better access to premium cabins.

Although I have not carried out a formal survey, I would say — based on my experience — that most airlines offer ZED Low fares to most others. But ZED Medium is not unusual. Sometimes, you might find an airline offering you ZED Low in Economy, but ZED Medium in Business. However, ZED High is quite rare.

Who exactly qualifies?

You can only use ZED fares if you work for a participating airline, are a spouse, parent, or dependent of someone who does, or are a retiree. And ZED benefits only kick in after the employee has been there for six months. Some airlines have liberal rules giving employees more flexibility in who they can share their travel benefits with when flying on own-metal. But don’t count on such policies carrying over into the ZED world. In other words, not everyone who might get own-metal travel benefits from a friend, partner, or family member will also get ZED benefits.

Pass agreements

Not everyone who qualifies for ZED fares in general will necessarily be able to use them on any given airline in the system. This is because each airline has a separate two-way agreement with every other participating airline with which it wants to work. These are often referred to as “pass agreements.” The term “pass travel” is often used to refer to non-rev travel generally. And some people refer loosely to ZED fares as “passes.”

Some airlines have better pass agreements than others. These agreements dictate not only whether you will be able to fly standby on a specific participating airline, but also whether you will pay ZED Low, Medium, or High. And they determine whether you will be eligible for First/Business Class. The agreements are generally reciprocal. So someone from Airline A traveling on Airline B typically gets similar benefits to an Airline B person on Airline A. But Airline A and B staff might get different benefits from one another when traveling on Airline C, depending on what agreements their airlines have with C.

Some ZED agreements provide for different rules for the actual employee and their spouse compared with, say, parents. For example, the employee and spouse might pay ZED Low, while a parent may pay ZED Medium. Or the employee and spouse might be eligible for Business, while the parent isn’t. All of this comes down to the individual pass agreements between airlines.

ZED fares and airline alliances

Bilateral ZED agreements are separate from wider global airline alliances — i.e., Oneworld, Star Alliance, and Sky Team. Although airline alliances can lead to enhanced ZED benefits among member airlines, this is not always the case. For example, you may find you don’t get Business Class on all the members of your airline’s alliance, while you do get it on some airlines that belong to other alliances.

However, there are other ways in which an alliance can lead to enhanced ZED benefits. One is if all members of the alliance commit to offering ZED Low to one another (at least in Economy).

Another is that you may get “boarding priority” over ZED travelers from airlines that are not part of the same alliance. It is important to understand that the term “boarding priority” in non-rev-speak means something different from “priority boarding” in the revenue travel world. It does not refer to what boarding group you’re in when passengers get on the plane. Rather, it refers to your rank on the standby list. If there are two ZED passengers standing by and only one available seat, then the person with higher boarding priority gets on. Staff travelers on own-metal always get boarding priority over all ZED travelers. And standby revenue passengers — typically ones trying to change their confirmed flight — always get priority over all non-revs. Alliance priority aside, boarding priority among ZED travelers is generally a function of check-in time.

Where can you go?

Generally, if you have ZED privileges on an airline, you can go anywhere that airline flies worldwide on its scheduled services. Occasionally, however, you’ll run into “embargoes,” where an airline cuts off specific flights for non-rev travelers even if it has empty seats. That generally only occurs when there is unusual pressure on part of the airline’s system, typically caused by issues out of its control such as airport-imposed limits on passenger volume.

Another time when you might not get on a flight even if there are empty seats is if it is weight-restricted. That can, potentially, occur on any flight for various operational reasons. But there are departure airports where it is more likely to occur, such as those with shorter runways and/or higher elevation.

The four ZED steps

There are four steps to using a ZED fare:

• Ticketing

• Listing

• Checking in

• Standing by

However, two of those — ticketing and listing — usually merge. And the other two — checking in and standing by — occasionally do. Next, I’ll walk you through all the steps, starting with ticketing.

Step 1: ZED fare ticketing

To use a ZED fare, you need a ticket. Unlike regular airfares, you do not buy these on the website or app of the airline on which you want to travel or on a public travel portal such as Expedia or Kayak. Rather, there are two specialized travel platforms that sell ZED tickets.

One of these platforms is called ID90. This name is a bit confusing. The reason is that ZED fares replaced an earlier staff travel fare type also called “ID90.” “ID” in the world of staff travel stands for “Industry Discount” and ID90 fares got you 90 percent off some notional full fare. Some old timers still talk about “ID90’s” when actually referring to ZEDs. But the ID90 platform where you buy ZED tickets on certain airlines is something different. And the tickets it sells are ZEDs, not the ID90’s of yesteryear.

The other platform for buying ZED tickets is MyID Travel, which is a subsidiary of Lufthansa. Far more airlines use MyID than ID90.

Both platforms have their pros and cons in terms of their user interface. And both have their occasional glitches and bugs. But you don’t get to choose which platform to use. Airlines either sell ZED fares through one or the other, not both. So you ticket on the platform used by the airline on which you want to travel. And if you non-rev on a bunch of airlines, you’ll likely end up using both.

Both platforms can be accessed only by those eligible to use them. Typically, you access them through your airline’s online travel platform for own-metal staff travel. But you may be able to access them directly with the log-on credentials you use with your airline. Some airlines also use these two platforms for managing their own-metal staff travel, but larger carriers tend to have their own portals for that.

Buying a ZED ticket is quite straightforward. In fact, it’s simpler and quicker than buying a regular revenue air ticket as you don’t have to shop for the best fare or deal with seat selection and other options or upsells.

Although you put in the date on which you want to travel, the ZED ticket is not restricted to that date. However, a ZED ticket issued for travel on one airline cannot be used for travel on another even if the date and route are the same.

All ZED tickets are refundable if you don’t use them. It doesn’t matter why you didn’t use it — i.e., whether you didn’t get on the flight, changed your mind, no-showed, or whatever. You can simply request a full refund of an unused ticket at any time within a year of its issuance. The refund system is pretty reliable in my experience.

It is fairly routine in the ZED world to ticket more flights than you will actually take, because it can make sense to ticket your back-ups when time may be short and as a precaution against the system being down at the last minute. However, neither of the two booking platforms is a model of clarity in terms of making it easy to spot unused tickets out of the list of ones you’ve bought in a ticketing frenzy. So you need to keep careful track of what you need to get refunded as the systems aren’t going to remind you.

ZED tickets generally have ticket numbers, just like regular tickets. In some cases, the tickets are issued by the airline you work for using their ticket number prefix. In most cases, however, they are issued by the airline on which you’ll be traveling. This also dictates which airline charges your credit card. ID90 and MyID themselves never charge your card for ZED tickets. Rather, the airline issuing the ticket does so.

If you want to take a multi-segment trip on the same airline — e.g., New York to Cairo via Frankfurt — you can do so on a single ZED booking. However, it can be more flexible to make separate bookings and this also makes refunds simpler if you don’t get on the connecting flight you were aiming for. It doesn’t impact the price to any material degree.

That said, one reason to do a single ZED booking is that it may enable you to check in for the connecting flight at the initial point of departure. That can have its advantages with airlines where online check-in is not an option. It might smooth your transfer and — if it means getting checked in sooner — help your position on the standby list if you are competing against other ZED travelers. Occasionally, you might even get a seat assignment on the connecting flight when checking in at your point of origin. That happened to me and my wife recently traveling on British Airways from San Francisco to Cape Town via London — which was really helpful as the connecting flight was pretty full. And, by the way, if you ticket a connecting route through London on a UK airline and transit within 24 hours, you avoid Heathrow’s brutal taxes.

Step 2: Listing

Although buying a ZED ticket entails specifying the airline well as the date and flight number for your intended travel, the issuance of the ticket does not necessarily mean you are in the airline’s system as someone who wishes to travel on that flight. For that to happen, you also have to “list” for the flight.

With most airlines, listing is done automatically when you buy the ticket. So ticketing and listing are part of the same transaction — just as ticketing and reserving are when you buy a normal revenue ticket.

However, some airlines require you to list separately after you have purchased the ticket. If you don’t do so, you won’t show up in the airline’s system (at least, not in the part that matters) — even though you specified the flight on which you want to travel when you bought the ticket.

Some prominent airlines that require you to list separately are American, ANA, British Airways (depending on whether they issued the ticket), Emirates, and Qatar. Sometimes you do so on the same platform on which you bought the ticket, but most airlines requiring separate listing have their own listing portals. At least one — ANA — requires you to call the customer service number, which is how it was generally done pre-Internet.

Automatic listing is definitely preferable. It’s not just that it’s quicker. It’s also more reliable. With separate listing, problems occasionally occur when for some reason the airline on which you want to fly has a problem recognizing a ZED ticket number issued by your airline.

Some airlines have rules, at least in theory, that you need to list a certain period in advance of the flight — say, 24 or 48 hours. That is not typical, however. Usually you can list until very close to departure. Even if there is a published rule to that effect, don’t assume it is enforced. If you do run into this with last-minute travel plans, there can be a workaround. If you are prevented from listing for a same-day flight, try listing for a flight a day later. That will get you into the airline’s system, and the check-in or gate agent may then be able to roll you forward by a day.

As to how you find out about the listing procedures for a particular airline, most airlines provide staff with details of all their pass agreements with other carriers on their own staff travel site or app. You can also look up procedures on what appears to be an official public ZED information site — www.flyzed.info. And MyID also has a section that summarizes available pass agreements for your airline when you log onto that platform.

Step 3: Checking in

Merely listing for the flight generally won’t get you on the actual standby list. You are in the airline’s system at that point, but you are not all the way where you need to go. To be fully on standby, you need to check in.

With many airlines, you can check in online using the same websites and apps as revenue passengers and at the same time — usually 24 hours in advance. Sometimes, however, non-rev passengers have to check in at the airport.

Outside the U.S., some airlines have special staff travel check-in desks at their main hubs. Examples I have encountered include British Airways in London, Turkish in Istanbul, Emirates in Dubai, Qatar in Doha, and Ethiopian in Addis Ababa. Typically, though, you use the regular check-in. Even if there is a staff travel desk, you may be directed to the regular check-in for flights to the U.S.A. on account of enhanced security measures.

Emirates even has a staff travel lounge near to its staff travel desk in Dubai. But don’t expect a fancy lounge with refreshments.

Step 4: Standing by

Some airlines will confirm you on a flight and give you a seat assignment at check-in. That is more common when you check in at the airport than it is when you check in online. But Lufthansa is notable for accepting you on a flight when you check-in online up to 30 hours ahead if the flight is sufficiently wide open. You can even change your seat assignment at the same time. Austrian — a Lufthansa affiliate — apparently does the same. You may come across others, but it’s unusual. (That said, with non-rev travel nothing is actually confirmed until the doors close. Not long after first posting this, I had a Lufthansa Business Class early seat assignment yanked when they were trying to accommodate passengers from a cancelled flight.)

Generally, you will not be confirmed until close to or during boarding, regardless of how many seats are open. That is more or less always the case with U.S. carriers. When that happens, you will usually get something called a “gate pass,” which looks like a boarding pass except it doesn’t give you the right to board — only to go through security to the gate in order to standby. You’ll get the gate pass either on the app — if the airline supports it — or at airport check-in. And, by the way, TSA Pre-Check works with gate passes in U.S. airports if your Known Traveler Number is in the system. All of that should be quite familiar if you’re used to own-metal standby travel.

However, some non-US airlines don’t give out gate passes and make you standby in the check-in area — both in U.S. airports and overseas — until more or less when the flight closes for revenue check-in. If you’re accepted on the flight, there can then be something of a rush to get through security to the gate. Likewise, there are some airports around the world that don’t allow gate passes even if an airline in general favors them. Hong Kong, for example.

Standing by at the gate is preferable to doing so in the check-in area. Not only does it avoid the last-minute hustle through security, but the facilities airside are generally far better than those landside. In particular, you can — if you are eligible and have time before you need to be standing by at the gate — hang out in a lounge.

Non-rev passengers rarely get lounge access on account of their class of planned travel (although I have come across exceptions). But non-revs can generally use lounges for which they qualify independently. Delta is the only U.S. airline that won’t allow non-revs into its lounges even if they have a valid lounge membership.

Getting a confirmed seat assignment the moment you show up at the airport and get to the check-in counter — as opposed to when revenue check-in closes — can be less stressful than being sent to the gate and made to wait. But late seat assignment can have its advantages. You may get a better seat at the last-minute — especially if revenue passengers receive upgrades shortly before boarding. Although you can always try to change your seat at the gate just before boarding, that doesn’t always work (especially overseas). On the other hand, if a flight is pretty full, locking into a decent seat assignment upon arrival at airport check-in can make sense when it is an option (which, again, it generally is not when traveling on U.S. airlines among others).

If you are standing by at the gate, you will either be paged to come to the podium for a seat assignment when you clear the standby list or — depending on the airline — your seat assignment will show automatically on the app and you may also get a text. Sometimes you find out multiple ways. Again, that should all be quite familiar if you’re used to own-metal standby travel.

Generally, it is not necessary to announce yourself to the gate agents before you are called. At least, not in the U.S. Indeed, one of the main non-rev protocol rules is not to bug the gate agents unnecessarily, especially if they appear to be busy attending to other things. But if you are somewhere in the world where you are unfamiliar with local procedures, it may be helpful to introduce yourself — just to make sure they know you are standing by. The same applies if you have arrived at the gate quite late when they might already have called standbys.

In the U.S., the screens at the departure gates of U.S. airlines generally display the standby list, with the first three letters of each passenger’s last name. But don’t expect to find those in other countries or at overseas carriers’ gates at U.S. airports.

Usually, ZED non-revs are offered the best open seat in the class of service for which they are ticketed. That includes seats for which revenue passengers would pay extra. But that is not always the case. On Emirates, for example, both ground crew and flight attendants are not allowed to assign non-revs open seats that command a premium with revenue travelers, such as exit rows or bulkheads, at least not if there are any other open seats.

If you are offered a bad seat, it can be worth gently inquiring whether there are other options. A gate agent might somehow assume seats closer to the front are preferable and, therefore, assign a middle there, when there may be an aisle or window open further back. Likewise, an automatically generated seat assignment might prioritize aisles and windows over middles, but not factor in empty adjacent seats. Occasionally, the initially assigned seat seems completely random — for example, a middle when there are open aisles and windows further forward.

If you don’t get on a flight, the airline’s system — or the gate agent — might automatically roll you over to the next one so that you don’t have to manually re-list. That is the norm with U.S. carriers. But don’t count on it with all airlines. You may have to start over.

A pitfall: Entry rules for transit destinations

Most readers, hopefully, will know to check the entry requirements for their intended destination — visas, etc. But it’s easy to overlook a quirk of standby travel when it comes to places where you might change plane while trying to get to your final destination. If you are a revenue passenger with a confirmed seat traveling from Country A to Country C, but changing plane in Country B, you usually need not worry about the entry requirements for Country B. Generally — although there are exceptions — you do not need a visa to transit through Country B without leaving the airport even if you would need one to enter that country.

But if you are non-revving on that same itinerary, and you do not have a confirmed seat from Country B to C, then you will likely not be able to board a flight from Country A to B in order to try to connect to C unless you meet the entry requirements for B. This is because the airline has no means of knowing whether you’ll end up stuck in B for any length of time. And airlines can be fined for allowing passengers to board a flight to a country without the paperwork to actually enter it.

So check out the entry requirements for any country through which you may want to transit regardless of whether you are planning on passing through its immigration. In many ways, non-rev passengers have a great deal more flexibility than their revenue counterparts. But this is an exception where there is an additional regulatory burden on non-revs.

Another pitfall: Dress codes can be stricter on non-U.S. carriers

Dress codes for non-revving on U.S. carriers have gotten pretty relaxed. Indeed, when non-revs are assigned seats automatically with an app, they typically don’t have any interaction with gate agents that could potentially lead to heightened sartorial scrutiny.

But when you non-rev on non-U.S. carriers — especially on flights departing from their home airports — you may encounter more old-fashioned approaches to staff travel dress codes. Middle Eastern airlines can be especially strict. I heard of a non-rev who was denied boarding by Qatar because he was wearing sneakers. I’m not sure what sort of sneakers they were. And I wouldn’t caution against all sneakers even on pickier airlines. I’ve worn all-black Hokas and Ons on all sorts of carriers. But you may want to keep dress codes in mind when in mind when traveling around the world on ZED fares, especially if you are standing by for a premium cabin. Try to dress the part.

Checking loads

One of the biggest challenges of non-revving on other airlines is knowing the loads. When you fly on own-metal, you can usually check exact loads on your own airline’s system. That luxury does not apply to traveling on other airlines. Fortunately, there are some ways of getting the information.

Both ID90 and MyID give you very rough guidelines about the available numbers of seats when you list. But you shouldn’t rely on these. For example, the MyID stats are based on information about the number of revenue seats the airline can sell in a single booking for each fare class and it comes up with green, yellow, or red bars — it used to be “smiley faces” — for each flight based on that. But that number of seats doesn’t necessarily correspond to the total that are available. There may be many more. Conversely, without wishing to get too technical, the number of seats shown in different fare classes does not total the number of seats even for a single booking because the same seat may be sold in more than one fare class (a “fare class” is not the same as a “class of service,” as each class of service may have a number of fare classes).

If all of that sounds a bit confusing (and it is), then the bottom line is that you should regard load information on the ticketing platforms with caution. I find the MyID “red” and “green” indicators can be a rough guide, but “yellow” can mean a wide range of things. And there seem to be some airlines that always show “yellow” regardless of load. Furthermore, even if you know the number of unsold seats, that information is incomplete without knowing the number of standbys already listed — which these platforms will never tell you.

The best way of checking loads is an app called Staff Traveler. This uses a crowd-sourced system in which airline employees share information by providing load information — including numbers of standbys — in response to requests by other users. It works on a points system. You earn a point for each load request you answer, and you pay a point for each load request you submit that gets answered. You can also buy points.

Staff Traveler is an excellent app. But its main limitation is that it is much easier to get responses for some airlines than others. You can generally get pretty speedy load reports for U.S. airlines (except that Delta loads are usually only available within a day or two of departure). However, load reports for airlines in other parts of the world can be a bit hit or miss in terms of when or even whether you get a response. Even within the same region, it can differ a lot. For example, I find load reports on Lufthansa usually come quite quickly. Those on Air France and British Airways tends to be less forthcoming.

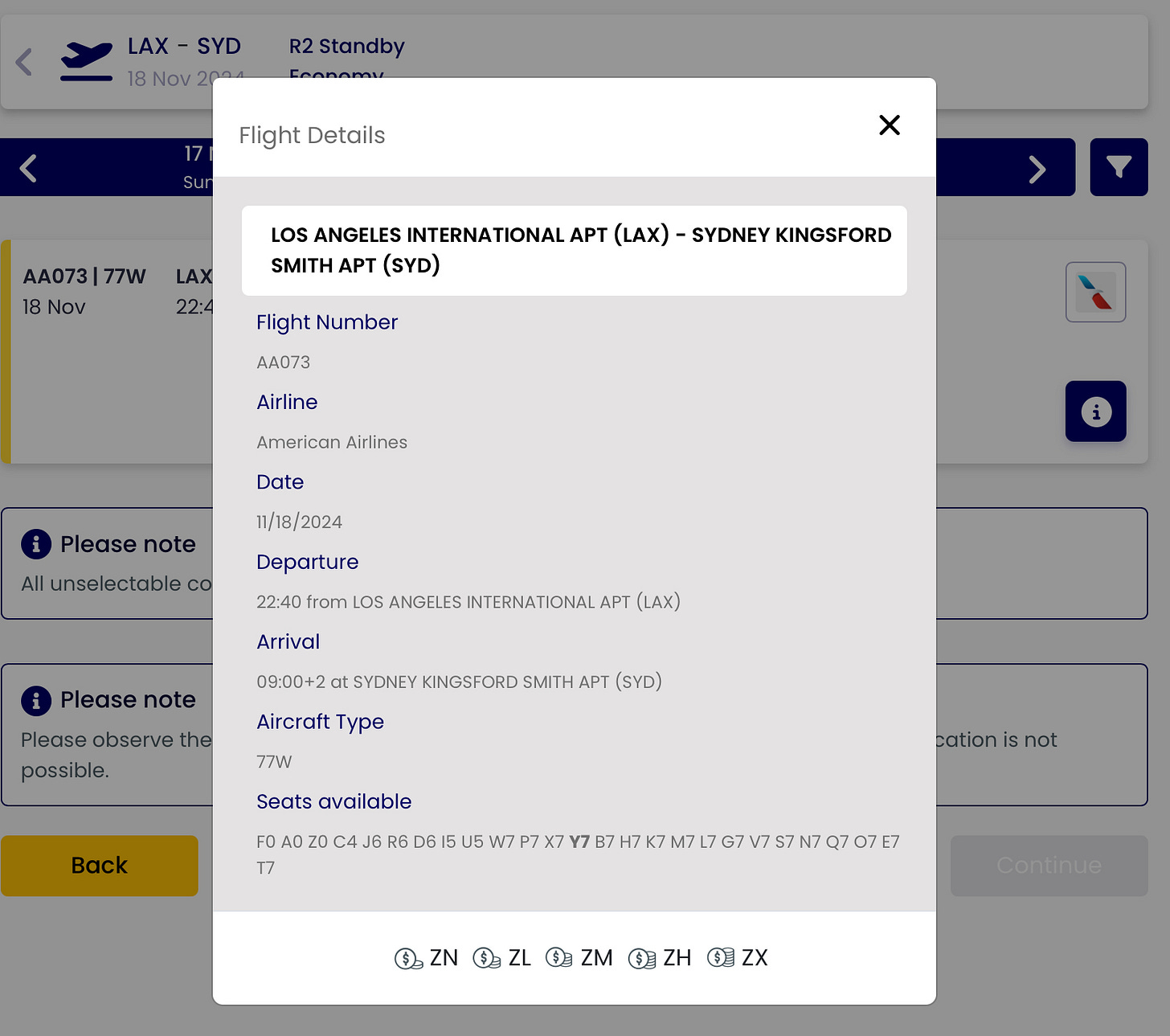

As an illustration of why Staff Traveler is far more reliable than relying on what you can glean about your standby chances on MyID or ID90, take a look first at the following MyID screenshot showing the loads on an American Airlines flight from Los Angeles to Sydney departing on the following day when the booking would be for ZED Economy:

This shows a yellow bar at the top left, suggesting the standby chances are, at best, moderate. And then there are numbers showing four to seven seats in various fare classes. So if you relied on that, you might think your standby chances were a bit iffy.

But now look at the screenshot for a Staff Traveler load report received at about the same time for that same flight (which I triple checked for accuracy):

So here you see that there were, in fact, no less than 70 open seats in Economy, even though MyID was showing “yellow” and giving what was essentially useless information regarding numbers of seats open for a single reservation in different fare classes. So relying on MyID for loads makes no sense. In the example above, the information was actually worse than useless. It was, in the overall context, misleading with its “yellow” bar.

Generally, the information on Staff Traveler is accurate. But it is, of course, only as good as the input from the person who responds to your request and, occasionally, a load report seems suspect or is plainly wrong or incomplete. Fortunately, the app automatically reopens your request without charging you another point if you submit an inaccurate load report.

Sometimes, even if the load reports are technically inaccurate, they are good enough. For example, quite a few people who submit reports mix up classes of travel so that, for example, Business is reported as First, and Premium Economy as Business. Likewise, quite often, responders leave a class of service blank, when they presumably mean to say there are no seats in that class. But one can usually figure out what the numbers are with those sorts of slightly imperfect reports.

The imperfections in Staff Traveler have nothing to do with the app itself, which is pretty glitch-free, but are a function of the crowd sourcing on which it relies. The app is nonetheless by far the best tool there is to assess your standby chances and is an indispensable tool for serious ZED planning. When you initially sign up, there is some light screening to ensure you are someone with staff travel benefits. The app is not available to the wider world.

If you are flying on a U.S. airline, you can also check the seating charts. That is not a very reliable method of assessing loads, as not all revenue passengers have assigned seating prior to check-in or even until boarding. And, of course, the seating chart does not tell you about standby loads. Nonetheless, seating charts can be a useful very rough-and-ready advance planning tool when you are low on Staff Traveler points and want guidance as to where to focus. If a chart shows hardly any unassigned seats, for example, that is a good sign that standby chances probably aren’t great. Keep in mind that airlines based outside the U.S. don’t generally allow you to view the seating chart until you purchase a revenue ticket.

Once you do check in as a non-rev, you may get some load information from the airline’s app and be able to view the standby list, but the quantity of data varies. The best airline app by far in terms of load data is United’s. Once you’re checked in, the United app tells you more or less everything a gate agent could until the very final portion of boarding — even the number of potential misconnects that might open up seats. However, the most detailed information there is a bit buried and easy to miss if you don’t know where to look (hint: go back to the “check-in” section, not the “flight status” section, even if you are already checked in).

Listing for premium cabins on ZED fares

The holy grail of non-rev travel is to sit in a premium cabin. As noted earlier, whether you have a shot at this depends on your airline. Some have pass agreements that allow you to list for ZED Business on a wide range of other airlines. But others do not.

What ZED Business gets you depends on the configuration of the aircraft. The simplest way of stating it is that ZED Business gets you into the highest class of service on any aircraft where there is space available — regardless of what that class is actually called — except on equipment where there is a First Class that sits higher than Business (a diminishing category).

There is no ZED fare that entitles you to space-available “First” on a flight where “First” is a higher class than “Business.” But if you are on a two-class flight with “Economy” and “First” — such as many U.S. domestic flights — then ZED Business is a ticket for First. (Where there is both “First” and “Business” on a given flight, First is always better than Business. But “Business” on a long-haul flight is generally better than “First” on a U.S. domestic one. The term “First” rarely, if ever, features on short-haul flights outside the U.S. these days.)

There is no ZED fare that specifically allows you to list for Premium Economy. However, if you list for Business but there isn’t space available, you’ll get seated in Premium Economy if a seat is available there. So for ZED purposes, Business and Premium Economy cost the same. Maybe, one day, the ZED “powers that be” will come up with a Premium Economy fare.

Getting into Premium cabins on ZED fares

Being entitled to list for Business is one thing. Actually getting to sit in the pointy end of the plane is another. These days, U.S. domestic premium cabins typically go out full even when there are open seats at the back. The reason is that free upgrades are given to frequent fliers with status. ZED non-revs are behind those revenue passengers when it comes to premium cabin access. You may occasionally find a domestic flight with more open First Class seats than upgrade-eligible revenue passengers, but it is increasingly rare. What’s more, as a ZED traveler, you’ll be behind staff travelers on their own-metal.

The story with long-haul international Business Class is different. Because these tickets cost a lot of money, airlines are reluctant to give them away as upgrades. They want their elite frequent flyers to pay for them. That, indeed, is what typically catapults someone into the highest levels of elitedom. The result is that ZED staff travelers are — perhaps counterintuitively — more likely to get a fancy lie-flat Business Class pod on a 10-hour international flight than they are to get a much less fancy First Class recliner on a two-hour U.S. domestic one.

The problem, however, is that even when there are, say, a dozen open Business Class seats on a long-haul flight, there are very often that many or more own-metal non-revs (who, as a reminder, will always be ahead of ZEDs on the standby list). That is especially when traveling on U.S. carriers. Sometimes when a flight looks wide open in Business a day or so ahead of departure, swarms of own-metal non-revs then appear on the list as the hours count down. In fact, the more wide open a flight is in Business, the more tempting it is to the swarm.

I have nonetheless got lie-flat while traveling on ZED Business on U.S. airlines, but I find my success rate lately has been significantly better on non-U.S. ones. The reason is that U.S. staff travelers seem to use their own-metal benefits more avidly, and in a more impromptu manner, than those from other countries. And not all airlines in the world are as generous in their travel benefits to their own staff as U.S. ones. If that reality drives you to try out different airlines, that can add to the overall ZED experience.

Keep in mind that your competition for Business in the hours leading up to departure isn’t just from other non-revs. Some airlines try to sell — or even auction off — last-minute, cut-price upgrades to revenue passengers booked in lower cabins. This is especially common among more leisure-focused airlines, although Qantas — a more traditional carrier — does this, too. And this can completely change what initially looks like a promising upgrade landscape in the 24 hours leading up to departure.

What if you pay for ZED Business, but get seated in the back?

As mentioned earlier, you pay extra for ZED Business. Personally, I find paying around $150 extra for long-haul Business Class to be well worth it. But what if you pay the money, but only end up being offered a seat at the back of the plane because there is no room at the front? Do you get you get a refund for the premium? The answer is maybe, but don’t count on it.

The default is that if you accept a seat in Economy when traveling on a ZED Business ticket, you do not get a refund. However, there are some airlines that will credit you the difference. This is more cumbersome than getting a refund on an unused ticket. It generally involves emailing the airline. And, to be clear, this option is usually not available. To find out what the deal is on a given airline, you need to review your own airline’s pass agreement with the other one, which should be available on its staff travel portal.

Absent partial refunds, you can’t get a refund. So your best option is only to list for ZED Business when there is a reasonable possibility you will get the premium product. That generally means never listing for ZED Business on U.S. domestic flights. The chances of getting a seat in the front are just too slim.

Another option is to buy two tickets and list on each, one Economy and the other Business. You can check in on one, but then cancel and switch to the other as departure nears depending on load information. And you can get a refund on the one you don’t use. (You are not meant to be checked in on more than one booking for the same flight at the same time, even though the systems might allow it. Don’t do that. But listing twice for the same flight is fine.)

However, the two-track approach doesn’t always work if you go down to the wire. Often, you won’t know whether you are going to sit in Business until very shortly before the doors close. Even if you have reliable load information, seats sometimes open up at the very last minute when revenue passengers who are checked in do not show. Or when other non-revs with higher priority fail to appear.

At that point, it may just not be practical to cancel yourself on one booking and then check in on another. It’s not just the time crunch. It’s also the fact that you may find that within 30 minutes before the door closes, it is no longer possible to cancel and then check in again without the help of a gate agent. And you will not be popular with gate agents if your personal stress dealing with this quandary becomes their problem during a very busy portion of ground operations. Also, you may go even further down the standby list if you cancel and then check back in.

So there are times when I just suck it up. If I’ve rolled the dice and lost, I console myself with the times when I’ve rolled and won. If I amortize the ZED Business rate over all my flights, it still looks pretty good. And Premium Economy can be a decent consolation prize if I’ve paid for Business. (Although I’ve turned down “upgrades” to Premium Economy when the seat at the back was better in terms of empty ones around me. Check out this post about “strategic downgrading.”)

Another option, of course, is to simply not board the flight in any class when you don’t make it to the front and then try for Business on another. But that depends on what other options you have and how much of a hurry you are in to get to your destination. Not to mention how comfortable a flight you’re likely to have in the back. Most often, I’m okay being at the back if I’ve played the game and lost.

Nonstandard upgrade benefits

There are airlines that offer staff travel benefits to people from another airline with which they have some alliance that include enhanced upgrade benefits. This can involve something priced similar to a ZED Economy fare — although, depending on distance, sometimes a little bit higher — which entitles you to space-available upgrades without paying extra to be listed for the higher class of service. That can remove the stress of which class to list for — the price is the same whichever you go for (except for flights out of the U.K. where taxes are higher when listed for Business regardless of the class in which you end up being seated). But that is the exception, not the rule.

Discretionary upgrades?

Personally, I never ask for an upgrade to which I’m not entitled according to the pass agreement on which I’m traveling. Maybe there was a time when things were different. But these days, computer systems restrict the discretion given to gate agents. So one reason not to ask for a discretionary upgrade is that you are very unlikely to get it. But another is that you are effectively asking the gate agent to do something that could get them in trouble and even jeopardize their employment. For the same reasons, I would never ask the cabin crew, either.

In fact, even asking could, potentially, lead to a report being made that might jeopardize your flight benefits. I heard of an incident not long ago when a gate agent apparently reported a non-rev who simply asked to be moved to an exit row in Economy. I think that gate agent was out of line unless there was more to the story. But the moral is that you never know who you are dealing with and you don’t want to do anything that might be misconstrued as inappropriate.

Occasionally, however, you may be offered a discretionary upgrade as a non-rev without having asked. I recall one occasion several years ago when I was settling into my transatlantic Economy seat on a U.S. carrier — on which at the time we did not have Business Class privileges — and a flight attendant whispered to me not to get too comfortable as she would move me to the front once the doors closed. The closing of doors is when jurisdiction over seating switches from gate agents to flight attendants. I hadn’t had any communication with her before, so this welcome news came out of the blue. And I recall another time when a gate agent on a domestic flight entered the cabin after I was seated in order to move me to the front when I had only listed for the back. Recently, my wife and I were on a short-haul flight within Europe where we were listed for Economy but given Business for no apparent reason — there were open seats at the back. But these experiences are rare. They are great when they occur, but don’t ever count on them.

Occasionally, you may get a discretionary upgrade if you are listed for Economy, but the plane is full at the back with some open seats at the front. This has never actually happened to me. This is, in part, because, as mentioned earlier, flights these days tend to fill up in the front. And even when this situation does occur, an airline might give last-minute complementary upgrades to revenue passengers rather than upgrading non-revs. Moreover, although the culture among U.S. airlines tends to be to try hard to get everyone on board, you may find airlines in other parts of the world that would leave a non-rev behind if the only empty seats are in a cabin higher than that for which they are ticketed.

Some non-revs bring small gifts for the gate agents or crew when traveling on other airlines. And, anecdotally, I have heard of that sometimes leading to upgrades (or failing that, to other treats such as bottles of champagne to take away). But you need to be careful. I think that is more appropriate if you yourself are a pilot or flight attendant. Since I am neither, I myself don’t do that.

But gifts can be nice when they are not self-serving. My wife recently gave a gate agent from another airline a Starbucks gift card after he had been unable to get us on a flight from Denver to Tampa. He had tried so hard and she wanted to thank him.

Conclusion and final advice

In conclusion, ZED travel is an amazing benefit. Yes, you pay something. But it allows for very inexpensive, flexible, and spontaneous travel to virtually anywhere in the world. And when you can get into the front of the plane, the monetary value of the benefit is even greater.

Much of my advice to ZED travelers is the same I’d give any non-rev — for example, ideally start with the earliest flight of the day, be flexible and have back-up plans, enjoy the ride, be nice to everyone, and so forth. But in terms of ZED-specific advice, I’d add these points:

(1) Check your company’s pass agreements. Ideally, go through them one by one. You’ll never know what the benefits are unless you look. I’ve only found out about some recent Business Class additions to our benefits by actually re-reading some pass agreements. And I only recently found out we have benefits on a major European private jet operator on its repositioning flights. And that was when I was told about them by someone from another airline — so I hadn’t actually followed my own advice. As a result, my wife and I recently had a memorable experience on a private jet between Nice and Amsterdam. The flight attendant brought out the champagne and the pilots couldn’t have been more welcoming. They were happy to welcome non-revs, because it meant they could participate in the system — which isn’t usually the case with private aviation. It was the ultimate non-rev flight experience.

(2) If trying for Business Class, try to focus on non-U.S. carriers in particular (assuming your airline’s pass agreements allow it). You’ll generally face less standby competition.

(3) Pay attention to dress codes as you ZED around the world. ✈️

Comments, suggestions? Please email: flyrun@substack.com

If you’ve stumbled across this post, please consider subscribing to this blog using the button below. It costs nothing — and never will — but supports the site. The site is not only about non-rev travel, but many of the posts do have a non-rev angle. You’ll get an email every month or two with new posts. For a list of other recent posts, click here.

And please share this post with others who may be interested, using this button: